LET’S GET DOWN TO BUSINESS.” As our middle school head opened the student’s folder, the rest of our middle school faculty got quiet. We’d convened to strategize how best to help Josh*, a new student who’d been kicked out of another school for “anger management” issues. When the conversation moved to what electives Josh would be taking, she turned to me, the theater teacher: “You want him?”

She knew what my answer would be before I said it: yes. Absolutely yes. Before I moved to California in 1998, I worked as a victim witness advocate in the district attorney’s office in Boston. After two years spent counseling survivors of domestic violence and families of murder victims, I realized I wanted to work with people to reach them at an age where it could really make a difference, through the mediums that meant the most to me when I was growing up. That’s how I became a creative arts teacher.

It is through this lens, of wanting children to feel connected and know their worth, that I now watch news of school violence, be it bullying, suicide or shootings. As an almost 20-year veteran of teaching music and theater to grades preschool through eighth in San Francisco and Marin, I believe creative pursuits can lead a child from isolation to a sense of belonging. Children in arts programs develop empathy, which just might be the necessary element to stop violence and cruelty in our schools.

*this name has been changed.

ISOLATION AS A CAUSE

In a nationwide survey released by health insurer Cigna in May 2018, 50 percent of respondents reported feeling lonely always or sometimes; younger people were more lonely and socially isolated than older generations. Research published in 2017 by psychologist Jean Twenge of San Diego State University suggests that the rise of digital and social media “may have caused a rise in depression and suicide among American adolescents” — and that people who spend less time looking at screens and more time interacting face to face are less apt to be suicidal or depressed.

Some even see social isolation as a “hallmark indicator of propensities for the type of homicidal psychopathy displayed by mass shooters,” as Steve Kadin and James Statler, who direct San Luis Obispo’s Community Counseling Center, wrote last November in an op-ed piece. They traced such isolation to influences like “early childhood neglect and abuse and subsequent low self-esteem; environmental factors combined with depression, anxiety and other mental illnesses; family criminal history; and feeling like a ‘stranger in a strange land’ — the loss of a sense of belonging.”

Increasingly, sense of belonging is considered “a human need, just like the need for food and shelter,” as psychologist Karyn Hall wrote in 2014 in Psychology Today. “Feeling that you belong is most important in seeing value in life and in coping with intensely painful emotions.” That’s not the same as craving approval, points out Brené Brown, a University of Houston research professor who has written extensively about the crisis of social disconnection. “Fitting in is about assessing a situation and becoming who you need to be to be accepted. Belonging, on the other hand, doesn’t require us to change who we are; it requires us to be who we are.”

CONNECTION TO SUCCESS

Creativity can lay the groundwork to promote that feeling of belonging, according to other research. A 10-year study by People United, an organization based in the United Kingdom, found that students participating in music, poetry, film, singing, or visual or performing arts showed more empathy, kindness, sense of community and social bonds. Now Americans are exploring that connection: the Minneapolis Institute of Art has used a $750,000 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant to establish the world’s first Center for Empathy and the Visual Arts.

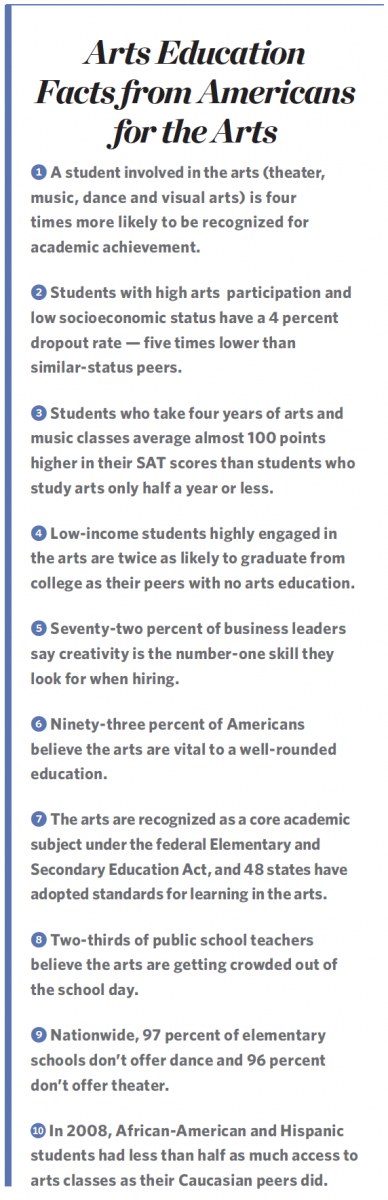

Experts are also seeing other measurable benefits of arts teaching, including “gains in math, reading, cognitive ability, critical thinking and verbal skill,” according to an article on the George Lucas Educational Foundation’s Edutopia website in 2009. Also, the National Endowment for the Arts research found that “at-risk students who have access to the arts show better academic results, better workforce opportunities, and more civic engagement.” And according to Americans for the Arts, “low-income students who are highly engaged in the arts are twice as likely to graduate from college as their peers with no arts education.”

LOCAL HEROES

If children are growing more isolated and the arts are an avenue for connection, why aren’t we doing more to make creativity part of curricula in schools? Even here in California, which used to lead the nation in arts education, Proposition 13, passed in 1978, together with the federal No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, shifted emphasis toward “teaching to the test”— curricula aimed at helping kids score well on standardized tests.

To fill the creativity breach, some Bay Area nonprofits have stepped up. In San Francisco, Michelle Holdt, a longtime theater teacher and arts administrator, founded Arts Ed Matters, to help give today’s youth the regular arts exposure and lessons she had growing up. “If I had to boil down my life’s work into one sentence, it would be that art heals and saves lives,” she says. “[We should be] helping children feel authentically seen, heard and valued, which enables them to feel safe to collaborate and take risks.” Working with school districts and groups, her organization provides workshops and coaching residencies to train teachers in arts curriculum design and techniques.

“Teaching to the test is isolating,” she says. “Children don’t learn by filling in bubbles. They learn by doing and touching and creating and playing — this is what creates engagement and connection.”

In Oakland, Destiny Arts, begun in 1988 as a dance and martial arts program, today also has classes in theater and new media arts, runs two pre-professional dance companies, and serves 2,500 kids at Oakland-area schools (including all West Oakland elementary schools), plus another 500 in after-school programs, summer camps and juvenile halls. All classes, offered free or on a sliding scale, include meditation and a check-in and emphasize a “Warrior Code” of love, respect, care, responsibility, honor and peace. “We believe that kids who are strong in their core and empowered to have control of their bodies are less likely to be violent,” says executive director Archana Nagraj.

Tesfaye Tekelu, a Destiny Arts teaching artist from Ethiopia, thinks that approach has a profound power to drive social change. “In my village, it was a community,” he says. “If I made a mistake, any older person would stop and guide me. … Children need mentors. If we see ourselves as human to human, not system to system, we create a compassionate community,” he adds. “Then we don’t need to be violent to be seen.”

Even in affluent Marin, programs like Youth in Arts still meet a need, particularly in higher risk Novato and San Rafael districts. Founded in 1970 to address diminishing arts access in public schools, the organization now serves around 7,000 kids at 59 sites and has reached over a million students since it began. Aimed at unlocking creative potential in people of all ages, the program also seats a student on its board. “We provide opportunities to choose a different path,” says executive director Miko Lee. “Personal violence and choices like joining a gang are often about finding a family. Our alums speak to having found family here.”

Not long ago I asked my former theater students how learning the performing arts might have affected their lives. “The stability of theater — and really being dedicated to a craft while simultaneously being supported by a community — has saved me countless times from depression and anxiety,” says Sophia, who graduated with an acting degree from Boston University School of Theatre last month. Jake, with a playwriting degree from Tisch School of the Arts, says, “Theater gave me a purpose that saved me from an isolation that, when married with my personal mental health cocktail, can be hard and painful. Without these opportunities, I wouldn’t have been violent, but I certainly would have been more self-hating, alone, and lost.”

And what about Josh? After an angry, and stunning, audition performance, I cast him as Macbeth. As his “behavior issues” persisted in other classes, in mine he used his rage and passion for good. Students who were once intimidated by him came to know and respect him. He made friends. He belonged. His performances were spectacular and showed his teachers and administrators a side of him they might not have seen had they just dismissed him as the “problem kid.”

Most importantly, when he confided in me that he was questioning his sexuality and asked me to help him tell his father, he let it drop that being involved in the theater had helped him reach this point. The experience, he explained, had made him feel he mattered — enough to be able to look at something that had been scaring him all along.

Genuine Therapy

The arts can be good for mental health: in a clinical setting, activities like music, art, drama, dance, movement, and writing have been proven to benefit children with social issues, developmental disabilities, ADHD, anxiety, depression and other conditions. To find an expressive arts/creative arts therapist in the Bay Area, contact your health insurance provider or a local mental health clinic, or use the search engine at psychologytoday.com

Emilie Rohrbach has taught music and theater to grades pre-school through 8th in San Francisco and Marin counties for the last 20 years. She has been a freelance writer for Divine Caroline for five years, and her writing has appeared in Narratively, Hippocampus, Common Ground, Travelers’ Tales, and Marin Magazine, among others. She is passionate about Room to Read, Shanti Bhavan, and Destiny Arts and serves on the board of Knighthorse Theatre Company.