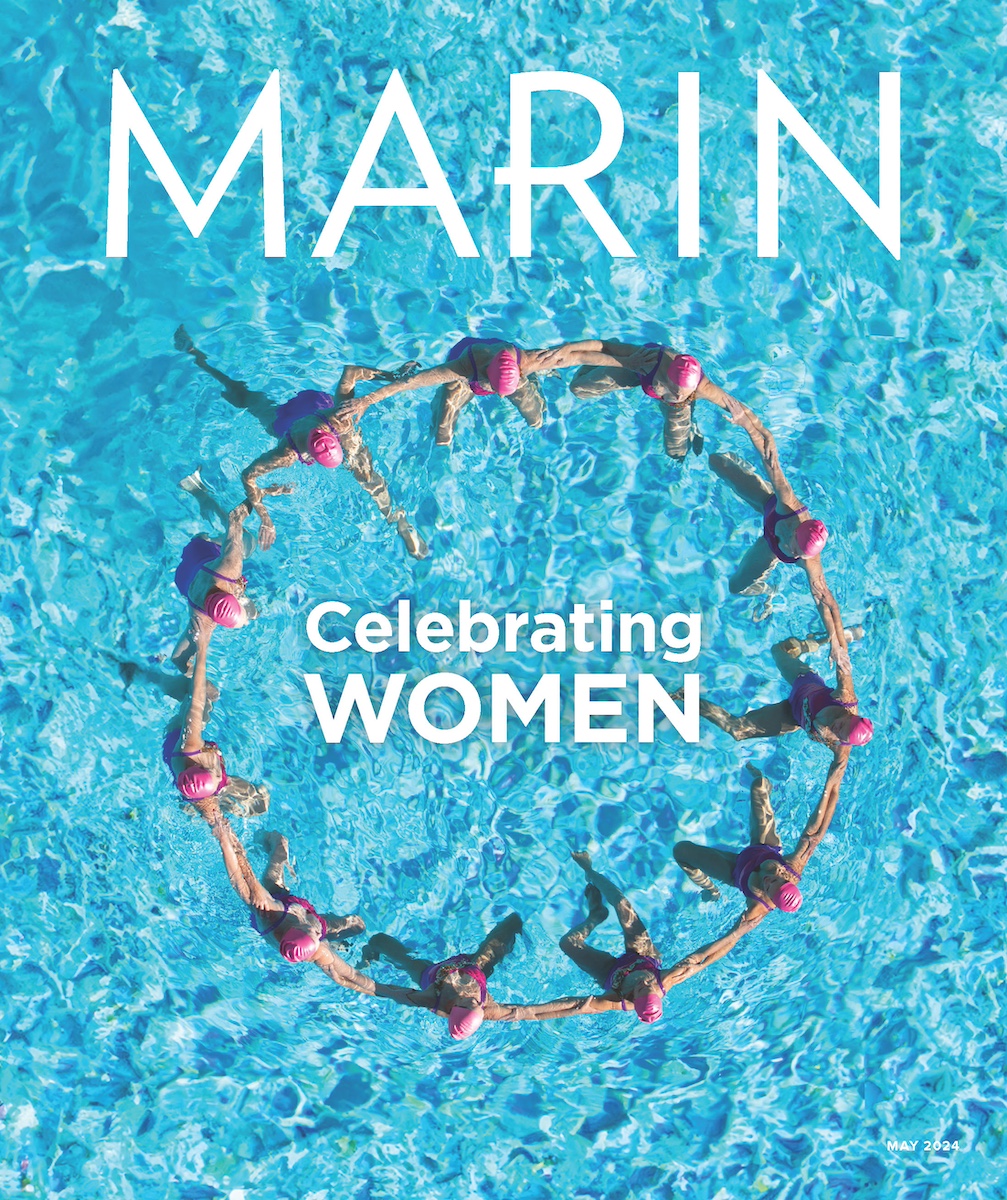

JUNE 10, 1967, was blessed: the weather was magnificent on Mount Tamalpais, where 30,000 to 40,000 people (by some estimates) were gathered for the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Festival. It could just as easily have turned out to be a typically cold and foggy Marin summer day — and in fact the event had been scheduled for the weekend before, then postponed on account of the weather. But June 10 was still early enough for Magic Mountain to go down in history as the world’s first outdoor rock festival, scooping Monterey Pop by one week and becoming the opening act of the Summer of Love.

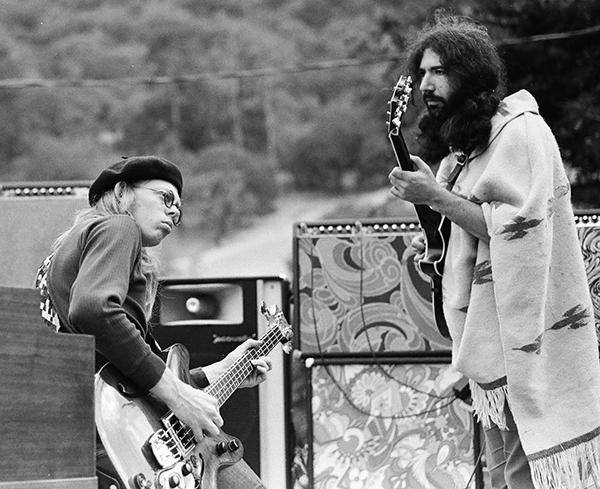

Photo by Radley Hirsch

Jefferson Airplane’s Spencer Dryden, Jack

Casady and Marty Balin rock the crowd at

the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Festival.

Outdoor shows were nothing new — bands like the Grateful Dead were known to set up on the back of flatbed trucks and play spontaneously in the panhandle of Golden Gate Park — but Magic Mountain was a first. Thirty-plus acts performed during the two-day charity fundraiser, including local bands like Jefferson Airplane (which had just hit the big time with Surrealistic Pillow in February 1967), Country Joe and the Fish and the Marin-based Sons of Champlin. Appearing too were Los Angeles artists The Byrds, Captain Beefheart, Canned Heat and a group named The Doors, fronted by a memorably intoxicated Jim Morrison, playing their first major show, which helped propel their breakout hit “Light My Fire” up the charts. The organizers chartered school buses to shuttle attendees and musicians up the mountain from Mill Valley, as Panoramic Highway had been closed to traffic. Those who missed the bus could catch a ride on the back of one of the Hells Angels’ Harleys. Price of admission to the festival: $2

While the Bay Area garlands itself for celebrations and retrospectives on the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love, it’s easy to overlook the crucial role Marin played in the moment, overshadowed as it may be by what was going on in Haight-Ashbury, the epicenter of San Francisco’s counterculture. But epicenters can be crowded, messy places, and by the mid-’60s those looking to escape turned their gaze across the Golden Gate toward Marin, where they could be close to nature, the rent was (then a bit) lower and there was room to explore.

There was also bohemian precedent: eccentrics, thinkers and artists had already converged on Marin, mainly in Sausalito. Zen philosopher Alan Watts had joined artist Jean Varda on his famed houseboat SS Vallejo in 1961, where the two began hosting soirees and salons with Gary Snyder, Lew Welch and Timothy Leary, among others. Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg took in jazz at Sausalito’s No Name Bar. “Sausalito was a wonderful place in those days,” recalls Al Engel, owner of the erstwhile Glad Hand restaurant, a favorite hangout for artists, writers and movie stars through the 1960s. “People were interested in music, poetry, painting and meditation. There was an emphasis on sharing and caring, which we don’t have today.”

By 1969 Sausalito was changing, a victim of its own cool. Rents rose, and Engel moved on to Stinson Beach, where he opened the Sand Dollar restaurant. But “I wish I could be back there now,” he says. “There was a renaissance of love and awareness and compassion, and the feeling was of great bonhomie.”

By the mid-’60s, Marin had become a refuge and incubator for San Francisco’s psychedelic vanguard. The Grateful Dead had been working on their sound — and their esprit de corps — over eight glorious, clothing-optional weeks during the summer of 1966 at Rancho Olompali in Novato and then later at a former Boy Scouts camp in Lagunitas. They practiced in a disused World War II munitions warehouse at the Sausalito heliport — as did Quicksilver Messenger Service, then residing in Olema. Big Brother and the Holding Company moved to Lagunitas in 1966 and began rehearsing with their new vocalist Janis Joplin and writing songs that would appear on their best-known record, Cheap Thrills.

At night musicians would jam, experiment and cross-pollinate at Sweetwater Saloon in Mill Valley and Uncle Charlie’s in Corte Madera, among other nightclubs. In 1966, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters held an Acid Test for the ages at Muir Beach, notable for being the first Acid Test attended by San Francisco’s acid king, Owsley “Bear” Stanley (who reportedly drove everyone there nuts by dragging a chair screechingly across the floor for hours on end). By the dawn of the Summer of Love, Marin had already long been a zone of playful weirdness and cultural ferment — its own, if more diffuse, epicenter.

Photo by ELAINE MAYES

The weather was great on Mount Tamalpias

in June 1967 for the Fantasy Fair and Magic

Mountain Festival.

“As I look back at Magic Mountain, I get a feeling of freshness,” says Jack Casady, then the bassist for Jefferson Airplane. “There were a lot of people up there on that mountaintop, a lot of variety of acts. It was exciting stuff.”

In some ways, Magic Mountain represented the culmination of an era rather than the launching of a new one; it would be among the last of the freewheeling hometown gigs for bands like the Airplane, which was ascending to cruising altitude just as the counterculture was heading further into the mainstream. “As soon as we finished playing, we jumped offstage and wandered into the crowd to watch the next act like other people would,” Casady says. By the following weekend at Monterey, “it got to where you couldn’t do that.”

But for Casady, as for many who were there, Magic Mountain wasn’t a watershed cultural moment. “We weren’t all thinking, ‘Well, this is a major-level change’ like when we played Woodstock, which was beyond anything else,” he says. “At the time we saw it as pretty cool, it worked out great and it was a way to open up and identify with more people.”

One of those people was photographer Elaine Mayes, who was then living off Panoramic Highway on Mount Tamalpais. She’d bummed a ride up to the Cushing Memorial Amphitheatre on the back of Hugh Masekela’s motorcycle (Masekela had come to perform with The Byrds) mainly to photograph the event, as she’d been documenting the Haight for a couple of years prior.

“There were kids sliding down the hill on cardboard. People selling trinkets and incense, painting faces, all kinds of people in the woods smoking pot — that was the most amazing thing,” she recalls. “There were cops everywhere, and nobody paid any attention. That had never happened before.”

That openness and freedom proved a boon to the young photographer. “I photographed Jim Morrison twice; you could get very close to anyone you wanted because there’d never been a festival like that before.” Like Casady, Mayes didn’t think of Magic Mountain as particularly momentous. “It was part of a process,” she reflects, “the culture was moving, and I was moving with it, following it with my camera.” A week later, Mayes photographed Monterey Pop; those images were published in her 2002 volume It Happened in Monterey, after languishing for decades in an archive. As for the images of Magic Mountain? They, too, perhaps are a treasure waiting to be rediscovered. “I have no idea where they are,” she says.

For Anna Halprin, the Summer of Love and the counterculture revolution dovetailed with the work she’d been doing since moving to Marin shortly after World War II. Through her innovation in dance, much of it based on improvisation, Halprin had already plowed and seeded artistic ground the hippies were only beginning to break.

Back in the late ’40s, Kentfield didn’t have much to offer a dancer who’d come from performing on Broadway. “There was no dance,” Halprin says, “but I wanted to be close to nature, near the mountain, the woods, the ocean.” Halprin’s husband built her an outdoor deck among the trees, where she developed radical new approaches to dance — so radical, in fact, that she was arrested in New York City after a 1965 performance of her pioneering piece, Parades & Changes, on account of nudity. “It was shocking to me, because here I am out in nature. Trees don’t wear clothes; why should we?”

That ethos appealed to the hippies, who found a kindred spirit in Halprin. “I was trying to work off the principles of nature. What is the nature of your body?” she says. “That approach liberates people so they can engage their own creativity. I wasn’t a hippie, but I could relate to what they were striving for.”

COURTESY OF OLOMPALI: A HIPPIE ODYSSEY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Jack Casady and Jerry Garcia jam in 1966

at Rancho Olompali in Novato

Halprin’s experiments struck a chord with musicians, too. Her dancers streamed down the aisles with banners at a 1970 Jefferson Airplane show, and Janis Joplin asked Halprin to come to one of her performances at the Haight’s Straight Theater and teach people to dance. “She wanted people to dance together. She didn’t want them to stand there waving their arms,” Halprin says. “That was my introduction to the hippies. My first company were all hippies — they all had long hair, they didn’t believe in shaving, everything had to be natural, their clothes were all very exotic, they wore whatever they wanted to. Everybody in Parades & Changes — the whole group — were hippies. They just stunned New York, because they were so creative, so imaginative and did the most outrageous, beautiful things.”

The outrageous, beautiful things coming out of Marin both before and after the Summer of Love continue to shape our imaginative reinvention of the time. The poster artists whose images gave the ’60s their signature psychedelic aesthetic — Stanley Mouse, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Alton Kelley and Wes Wilson — lived or worked in Marin. Clothing designers like Helene Robertson, whose eclectic, retro chic appealed to the hippie sensibility, attracted a willingly flamboyant clientele to Anastasia’s, her Sausalito boutique. Designer Melody Sabatasso, aka Love, Melody, drew a highbrow clientele — Lauren Bacall, Elvis Presley, Mick Jagger, Cher — with the most lowbrow of garments: Levi’s jeans, which she transformed into sequined jackets, dresses, jumpsuits and more from her eponymous San Anselmo boutique. Tie-dye artist Courtenay Pollock, having abandoned a construction surveying career in London, crossed paths with members of the Grateful Dead quite by chance in Nicasio Valley; his dyes graced the band’s speaker covers not long after, and still today tie-dye remains an inevitable feature at any jam band performance.

Although the organizers of Magic Mountain were praised in local media for leaving the grounds as clean as they found them, it’d be another 46 years before a rock festival would again be permitted back to the Cushing Amphitheatre. In 2013, producer Michael Nash staged Mount Tam Jam, with a multi-artist lineup that included Taj Mahal, Galactic and Cake. This September 9, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love, Nash will be bringing another rock festival, called Sound Summit, to the mountain.

The festival, with a lineup that is TBD, will be “a resonant celebration of and benefit for Mount Tamalpais State Park,” says Nash. “We’re trying to put together something that honors the spirit of the Magic Mountain Festival. It’s musical hallowed ground, so it’s great to rekindle something there.”

Sound Summit is one event among several to commemorate Marin’s role in the hippie era. On June 10, exactly a half-century after Magic Mountain, the Mountain Play Association will hold its own one-day Magic Mountain Play Music Festival at the Cushing Amphitheatre, with live bands, including Jefferson Starship, and a concert production of Hair. A de Young Museum exhibit, The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll, features posters and clothing by Marin artists and runs April 8 through August 20.

Fifty years on you can still find echoes of the 1960s in Marin, especially in musical hotspots like Mill Valley’s Sweetwater Music Hall, reopened in 2012 by Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir among others, or Dead bassist Phil Lesh’s Terrapin Crossroads in San Rafael, which the legendary band called home after 1970. But for the most part Marin today is a very different place than it was in 1967, one in which most of the creatives who drove the ’60s could never now afford to live. The county’s contemporary affluence, however, and its concentration of intellectual capital owes much to those cultural pioneers who strove to define a new vision of community.

“We really did think the world was changing for the better around us,” says Casady, now 73. “Then all of a sudden the next thing you knew, it was disco and drugs and you were laughed at for having long hair. And this was what, 10 years later? But that doesn’t nullify anything that was good about what the ’60s stood for, which was plenty. Every young generation has to find its purpose, and that generation finding its purpose boosts along everybody.”

Even if, at the time, that purpose is just trying to have some fun. “I have great, fond memories of Marin, of Mount Tam and of playing shows,” Casady says. “It was exciting just to have enough money to put gas in your car and drive around, smoke a joint and watch the beautiful sunsets in Marin County. That was a great day.”