In the 1890s — even before Einstein developed his Theory of Relativity —scientists believed electric and magnetic forces existing in the atmosphere could be electrically activated to carry energy. One such visionary was Italian physicist Guglielmo Marconi, who in 1914 had the Marconi Wireless Receiving Station built in the West Marin village of Marshall. At the same time, Marconi also built a high-power transmitting station on the Bolinas mesa. Then in the late 1920s, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) enlarged the Bolinas facility and constructed a new shortwave receiving center out on the Point Reyes Peninsula.

These three multistory structures, all made of concrete, are still standing, though hidden by tall stands of pine and eucalyptus trees (save for the towering antennas, readily visible to passing motorists in Bolinas and Point Reyes).

The energy these outposts generated and received were known as radio waves—swells of electric and magnetic energy that rolled through the atmosphere above the Pacific Ocean—similar to those on the watery surface below, although at the speed of light. And because radio was in its infancy, the antennas in Marshall, Bolinas and Point Reyes dealt almost exclusively in Morse code (SOS came across oceans as “. . . – – – . . .). Marconi was a pioneer in this emerging technology—and West Marin, through World War II, was one of its frontiers.

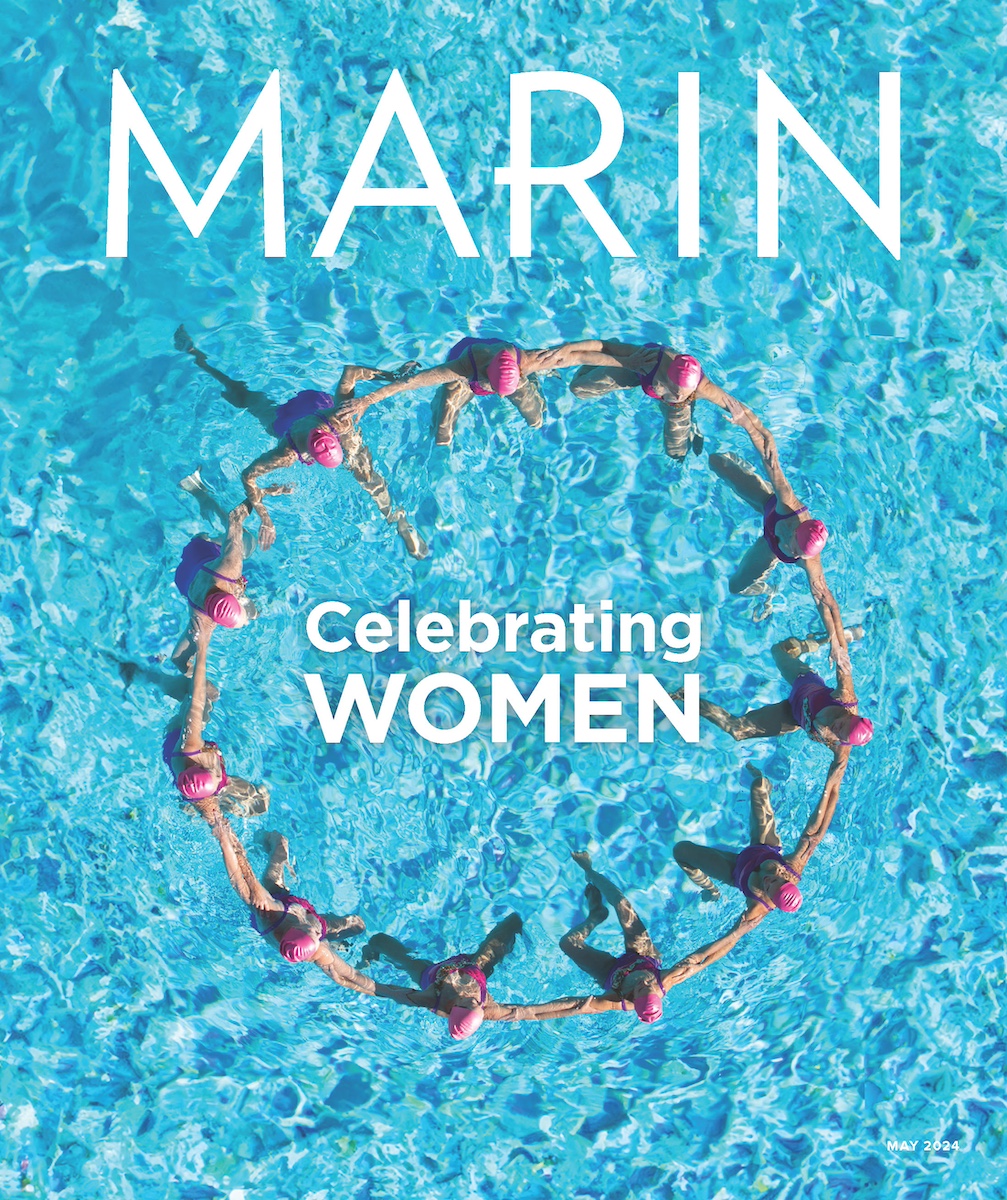

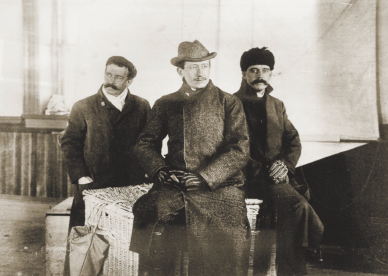

Guglielmo Marconi first made history in 1901 when, at age 28, his Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company sent a radio signal 2,170 miles across the Atlantic Ocean from Cornwall, England, to St. John’s, Newfoundland. In 1907 he started the first commercial transatlantic wireless service. Two years later he won the Nobel Prize for Physics, but his fame truly soared in 1912 when SOS messages brought rescue ships to the sinking Titanic, saving over 700 lives. Soon Marconi’s goal was to see a series of high-powered wireless transmitters erected around the world, which is how stations came to be located in towns like Marshall and Bolinas.

Why specifically West Marin? In 1905, the Palace Hotel, using, appropriately, the call letters PH, became home to San Francisco’s first radio station. International rules soon dictated that a K be added, and in 1912, Marconi acquired KPH as the result of a merger with his competitor, United Wireless. “After the earthquake of ’06, and struggling with less-than-ideal sites in Pacific Heights and Daly City, Marconi’s group considered the West Marin properties as ideal for reaching Hawaii with radio signals,” recounts Richard Dillman, a Point Reyes Station resident active in the Maritime Radio Historical Society. “Bolinas would be for transmitting and Marshall for receiving.” Both facilities were operational by late 1914, making transpacific wireless communication possible not only with Hawaii, but from there, also Japan and Hong Kong.

The Marshall complex included a power station, a signal-receiving center, homes for the station’s executives and their families, and a four-story hotel for the center’s unmarried personnel. “That four-story, 37-room hotel can easily be seen from Highway 1,” says Stephen B. Murch, a San Anselmo architect who’s overseen $1.96 million worth of construction and restoration at what’s now the Marconi Conference Center and State Historical Park. “People are always welcome to explore the grounds of the Marconi Conference Center,” he adds.

Except for the huge hotel, the old buildings still standing have been beautifully restored and now serve as staff quarters or conference facilities. “Only the concrete cable anchors remain from the 275-foot antennas that once dominated the site,” says Murch. “However, there is a museum display of radios, transmitters and teletype logs.”

Adding to the site’s mystique, from 1965 to 1980 it was world headquarters for Synanon, the statewide drug rehabilitation program that eventually disintegrated under indictments for child abuse, money laundering and tax evasion. According to architect Murch, the hotel, once a Synanon dorm but now boarded up, still has the garish green shag carpeting left over from those days.

During World War I, the U.S. Navy took over operations of both radio transmitting and receiving stations, Dillman says. And after the war, “the U.S. government realized the significance of radio communications and began to control it,” he adds. “Somewhat as a result, RCA bought the American Marconi Company and with it, Marconi’s dream of owning a worldwide communications network.”

As for Marconi’s Bolinas facility, located out Mesa Road four miles from town, Dillman of the Maritime Historical Society says, “The original buildings, those built by Marconi American, are behind the two-story concrete structure that was constructed by RCA in 1929.” According to him, “that white art deco building still bears the set-in-concrete title ‘RCA Communications Inc.’” However, for the past 30 years it’s been the headquarters for the renowned health and environmental think tank Commonweal. “And some old radio transmitters are still up on the second floor,” reports Commonweal general manager Waz Thomas. “Of course, the huge antennas are easily seen from Mesa Road.”

And those towers haven’t fallen completely silent. “Every Saturday morning,” says historian Dillman, “a bunch of us convene what we call the Church of the Continuous Wave and, just for the drill, send Morse code signals out from the Bolinas station and receive replies from ships at sea at the Point Reyes facility.” He’s quick to mention RCA built both buildings some 80 years ago.

“And once a year, on April 26,” Dillman adds, “we communicate with other stations around the world.” Why April 26? “That’s International Marconi Day. It’s the day Guglielmo Marconi was born in 1874.”

Captions:

Middle: Teams of horses were needed to transfer concrete building materials once they reached the Marshall job site by rail. Bottom: Guglielmo Marconi, pictured with two assistants, was 28 years old when he engineered sending a signal 2,710 miles across the Atlantic Ocean from England to Newfoundland (where this photo was taken).