Few things were more exciting when I was young than my family’s yearly trip to visit my great aunt Barbara in Belvedere. Although I grew up in the Central Valley, my family has roots in the Bay Area, and long before I was born, she had settled in Belvedere in a house known locally as “The Pagoda House.”

Visiting there was magical. From the street, the house’s pointy roof peeked out from behind a large, wooden, Asian-style gate. Inside, a narrow bridge passed over overgrown gardens, leading to a low, rounded doorway. In my imagination, it was like a gateway to another world.

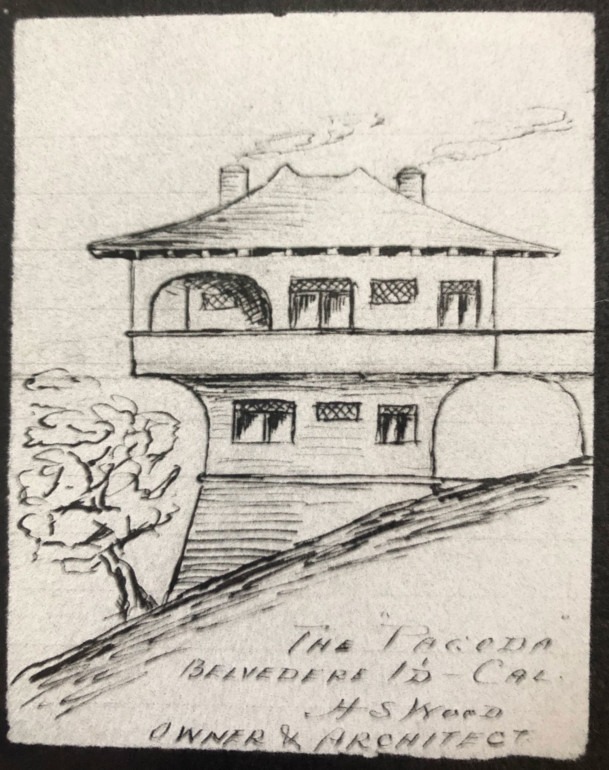

At the entrance to the house a large plaque designated it an historical residence dating from 1896, which had always piqued my curiosity. What I didn’t realize until later, when I began researching the structure, was that this was one of Belvedere’s first homes, and how much it embodies the history of this unique community.

Belvedere’s Beginnings

Belvedere began, like many parts of the Bay Area, as farmland, before being transformed into a military outpost. It only became a residential area in 1896 — the city celebrated its 125th anniversary this September.

Belvedere was a planned community. It was developed by the Belvedere Land Company, which sold off plots of land beginning in 1891 that were bought up and built — the Pagoda House was one of the first. In some of Belvedere’s earliest photos, the house sits jutting out on the hill, surrounded only by trees and a few other homes. It was built for Henry Shotwell Wood, an engineer for the S.F. Bridge Company, and constructed by Daniel McLean, who built many early homes in the area.

Before Belvedere was developed, the island had a large codfish processing plant. “The West Shore and its fishery predates the Land Company,” explains David M. Gotz, the archivist for the Belvedere-Tiburon Landmarks Society. “They were there until 1939 when the Union Cod Fishery building burned down.” The fishery was owned by John William Pew, who was also a town trustee, the commodore of the Corinthian Yacht Club, and one of the signees who approved the incorporation of Belvedere — and it was Pew who purchased the Pagoda House from Wood in 1897. According to a Sausalito paper cited in Life in Belvedere and Tiburon 1890–1900, he made his purchase there, as “prices are too high in Sausalito.”

The Bay Area’s International Architecture

Many houses dating from Belvedere’s early years were built with a similar layout that hugged the hill, with the residential portion at the top and the kitchen down below. In my childhood visits, venturing down the house’s narrow, creaky stairs meant encountering Koki, an obnoxiously loud cockatoo who screamed from his bay view perch while my great aunt stood nearby in the kitchen, chopping vegetables.

From the lower level you could walk out onto the deck and get a view of the unusual shape of the house from below. The building was squat and flat at the top, abruptly transforming into a dramatic downward curve at the base, as though it were being pulled down the steep slope. Alongside the overgrown garden with a teahouse nestled in one corner, a pathway descended dramatically downward; this was Pagoda Lane, framed by vines and heady with the fragrance of nasturtiums. It was Asian, yet at the same time, very much of Belvedere.

The Pagoda House’s shape was most likely inspired by the connections that the San Francisco Bay Area had with Asia during this time. While this was the only Asian-style building to be found on the island, the house no doubt must have taken its cue from some of the Asian-inspired architecture that was popular around the turn of the 19th century. For example, San Francisco’s Chinatown, built only a decade later after the earthquake, showed off just how invested Western architects were in the idea of the pagoda, which most of them had never seen in real life. As Chinatown was a fantasy idea of what Asia was, the Pagoda House was, too.

From the beginning, Belvedere’s residents seem to have had a fascination with the international, and this was reflected in the town’s traditions, as well as its architectural styles. Pew was the one of the organizers of the opulent “Night in Venice” festivities; its 1895 event attracted 30,000 spectators from around the bay to see a parade of the famed ark houseboats. According to a paper at the time, The San Francisco Call, it was quite spectacular: “Like beacons to all mankind the red and green and yellow lights glittered and flashed across the water like a million tongues of fire.” One ark, which was hailed as best decorated, was adorned with no less than two giant paper mâché lions, fishing nets containing 3,000 carnations and 500 colorful lanterns.

As Belvedere’s homes were originally built as summer retreats for the San Francisco elite fleeing the heat (and stink) of the city, the architectural styles here tended to veer toward the eclectic. “In the 1890s, families came over and stayed in what were mostly cottages, summer houses and arks,” explains Gotz. “After the earthquake in 1906, a lot of them just moved over.”

Belvedere has its own unique style of architecture known as First Bay Tradition, which combines an English and Swiss cottage sensibility with a heavy use of shingles. Some of the opulent architecture that sprung up on the island was influenced by the 1893 Columbian International Exposition in Chicago, which showcased the City Beautiful movement, bringing Beaux-Arts classicism to buildings across the country. Later, beloved Bay Area architect Julia Morgan was responsible for several Belvedere homes on the island, including part of lawyer Gordon Blanding’s grand classical estate that at one point required 25 employees to run. The center of it was Locksley Hall on Golden Gate Avenue, today one of the most expensive homes on the island. There was also “The Organ House,” which was enlarged to accommodate a massive organ that was eventually moved to the Paramount Theater in Oakland.

Art on the Bay

My great aunt and uncle moved to Belvedere in 1955; she was an artist who had studied at UC Berkeley and the Chicago Art Institute, and he was a graphic designer. She was also an art teacher and a children’s book author, publishing a book called The Otter Twins, which was inspired by otters she viewed at the San Francisco Zoo.

No doubt Belvedere’s thriving art scene had something to do with their move there. Art was part of Belvedere life since the town was built. “There were a lot of artists here,” explains Gotz. “A group of artists known as the ‘The Society of Six’ started a movement here in the late 19th century and early 20th century. They were inspired by the French Impressionists, which they would have seen at the Pan Pacific Fair. They applied this French Plien Aire style to the Bay Area; one of them, Seldon-Connor Gile painted an epic painting of the Tiburon/Belvedere waterfront.”

Many local landmarks, like the Organ House, were gathering places for artists and writers. Belvedere’s famous arks floated in the bay for several decades before they were relegated to shore in 1939, and were rented by artists and sculptors in the 1950s and ’60s, creating a small artists’ colony. It was home to well-known local artists like John Falter, who painted covers for The Saturday Evening Post magazine; Esther Meyer, a prolific landscape painter and water colorist; and Bob Bastian, who was a cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle and KQED.

My great aunt died in 2010 after living in the Pagoda House most of her life. The house’s walls were decorated with her abstract paintings, which were created in her studio with its panoramic views of Corinthian Island, Angel Island and San Francisco. Perhaps the shades of this landscape inspired her work. Undoubtedly, both her art and life were entwined with the history of her unique house and the beautiful community it’s part of.

All modern photos of the house courtesy of Adam Gavzner, Compass.

For more on Marin:

- A Love Letter to Belvedere: A Nostalgic Journey Into an Idyllic Childhood

- I Never Really Left Belvedere: Paige Peterson’s Story

- Gile’s Belvedere-Tiburon Mural

Jessica Gliddon is the Group Digital Content Manager for Marin Magazine. An international writer and editor, she has worked on publications in the UK, Dubai and Cape Town. She is a graduate of UC Santa Cruz, and is the former editor of Abu Dhabi’s airline magazine, Etihad Inflight. When she’s not checking out the latest exhibit at SFMOMA or searching out the best places to eat and drink near her home in San Francisco, she volunteers at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito.